Music

OPINION: Should The History of The Blues Be Rewritten?

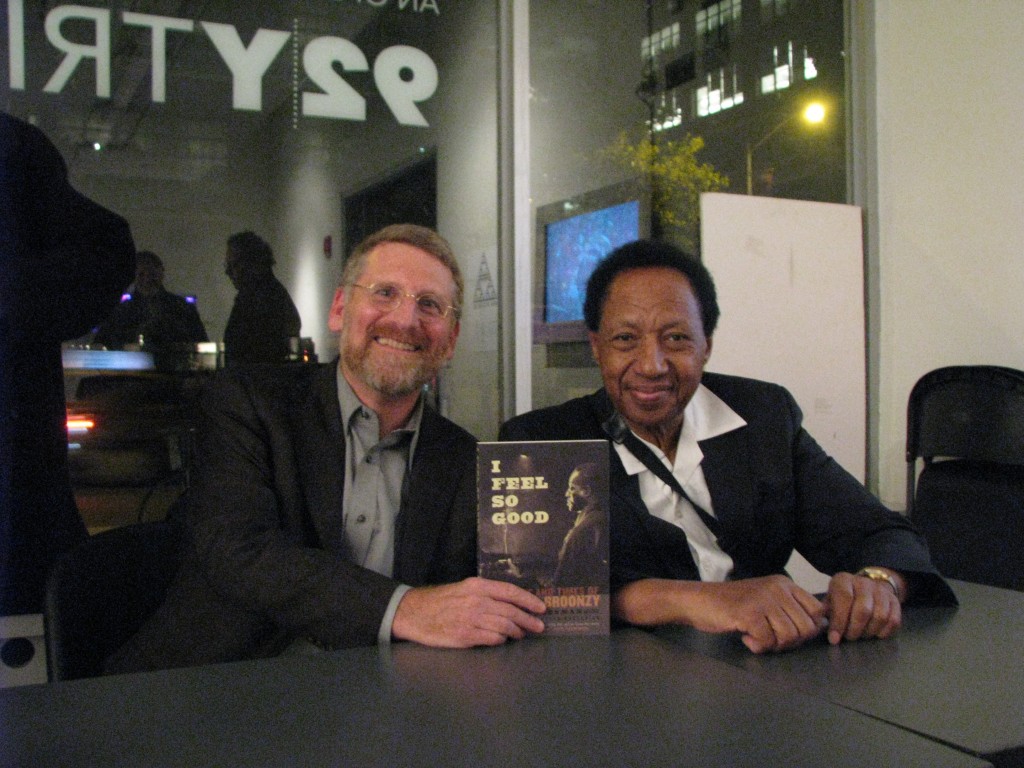

[caption id="attachment_55770" align="aligncenter" width="614"] Author Bob Riesman, left, with Billy Boy Arnold[/caption]

Author Bob Riesman, left, with Billy Boy Arnold[/caption]

The blues is a genre steeped in history, mythology, and the intersection between the two, with giants from the Delta's Robert Johnson to Chicago's Muddy Waters, Memphis' B.B. King to Texas' Stevie Ray Vaughan, all contributing to its legacy. But one figure who has been largely marginalized by history is Big Bill Broonzy, whose Arkansas roots, influential Chicago recording sessions, European tours and relationships with everyone from Waters to Pete Seeger made him a leading figure of his time.

Whereas Johnson's legacy is shrouded in mythology and Waters' largely committed to tape, Broonzy existed at that nexus between history and storytelling that bridged the gap between the two, and his life story is intertwined with both eras. That left biographer Bob Riesman with a substantial task to sift through the truths, half-truths and fabrications to find the facts for his extensively-annotated book "I Feel So Good: The Life And Times of Big Bill Broonzy," out in bookstores now.

Last Thursday night (Oct. 11), Riesman celebrated the paperback release of the book with a conversation with and performance by blues harmonica player and singer Billy Boy Arnold, who met Broonzy as a 15-year-old in 1951 while living on Chicago's South side, and released a tribute album called Billy Boy Arnold Sings Big Bill this past April. Arnold ran through an eleven-song setlist of Broonzy covers with guitarist Eric Noden, including gems such as "Key to the Highway" and "Just A Dream," a track that Broonzy performed in 1938 at Carnegie Hall for the From Spirituals To Swing concert, which he was asked to participate in after producer John H. Hammond learned of the death of Robert Johnson.

That Broonzy was the first choice to replace Johnson speaks to his influence even then, at a time when he was still early in his recording career. While Riesman keeps his assessment of Broonzy's legacy rooted in the facts, his book gives off the sense that Broonzy epitomized more of the African-American experience during the 1930s, 40s and 50s than any other single blues musician of the era, and it's a point that Arnold stressed more explicitly.

"People talk about Robert Johnson. Johnson's career lasted about six or seven years. Big Bill's lasted [thirty] years," said Arnold in an interview before his performance. "I'd never even heard of Robert Johnson until 1960, when Columbia put out Johnson's album. I didn't hear Robert Johnson's music in Chicago. Big Bill was a giant in the world of blues. Somebody had put the word out that Robert Johnson is The One, and so [his music] went on to make millions."

Re-writing the history of the blues was not the point of Riesman's book, nor of Arnold's tribute album. But spotlighting overlooked players and re-ordering the hierarchy of influential past masters is a side-effect of both.

"I believe [Broonzy] should be recognized more than he has been in recent years for his successes," said Riesman, relating how Waters was lead pallbearer at Broonzy's funeral, and was widely quoted as saying about his mentor, "Mostly, I try to be like him." "When [Broonzy] died, there was an obituary in the New York Times and in Time Magazine, national mainstream recognition, and in some ways his star waned afterward. I hope this shines a light on Bill in a way that hasn't been done in a long time."

Of course, resurrecting the careers of blues musicians is a practice almost as old as the genre itself, and many of Broonzy's contemporaries benefited from that tradition. Eric Clapton has shown a dedication to the haunting music of Johnson throughout his career -- since covering "Ramblin On My Mind" on John Mayall's Bluesbreakers album in 1966 -- and wound up recording two tribute albums in the last decade dedicated solely to his music. Howlin' Wolf's 1971 London Sessions album saw him backed by some of the best crop of British bluesmen around at the time, such as Clapton, Steve Winwood, Charlie Watts and Bill Wyman. And Stevie Ray Vaughan made sure to bring his heroes along with him, performing multiple times with Buddy Guy and recording his In Session album with Albert King.

Broonzy's ability to evolve his own styles -- from straight Delta blues, to hokum jigs, to Chicago electric blues, to folk music with his friend Seeger -- almost made it unnecessary for his music to be resurrected while he was alive, and perhaps that is ultimately why he is on the fringes of the popular history of the blues. His time may yet be here.