Design

ART REVIEW: Salvador Dali: The Making of an Artist

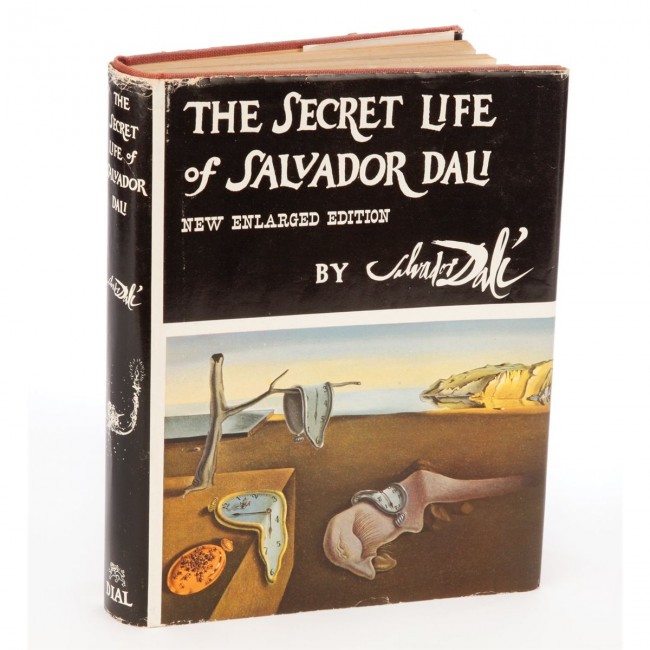

As a kid my favorite artists were everyone else's: DaVinci, Picasso, and Salvador Dali. I stumbled across art in an old encyclopedia set that was given to us by a lady whose house my mom cleaned. Maybe before that, but this is when I started paying attention, and we didn't have an extensive library in our apartment. There were very few color plates in this older set of books. But of all of these artists, few had the coveted 3 color process pages to display their work, yellowed and off colored. The Persistence of Memory by Salvador Dali was my favorite of these. It looked much when better when I first saw it in person at the MOMA as a sophomore in high school. I even thought I had become a surrealist back then, painting melted trees and the floating objects of my subconscious over landscapes, 60 years behind the movement.

[caption id="attachment_64859" align="alignnone" width="650"] The Persistence of Memory, Salvador Dali[/caption]

The Persistence of Memory, Salvador Dali[/caption]

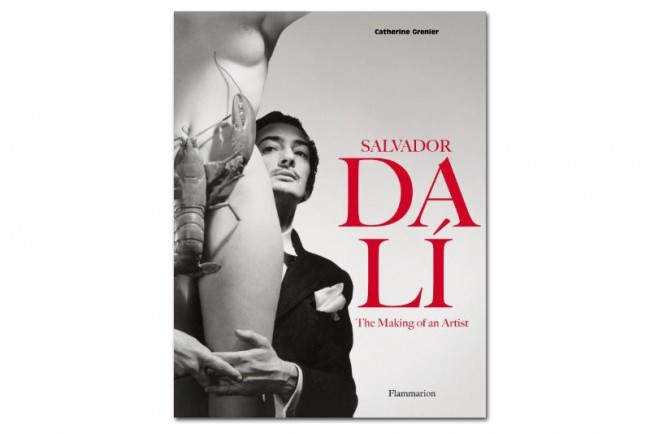

Years later and hopefully wiser, living in my own time, I was extremely excited to get an advanced copy of Catherine Grenier's Salvador Dali: The Making of an Artist, on Flammarion/Rizzoli. There are never too many books on this subject, or conversations I could have about the artist. I've read the "autobiography" The Secret Life of Salvador Dali, visited the Salvador Dali Museum in St. Petersburg, Florida as a student at the Ringling School of Art, and have come across his works in other galleries and museums, in film, at a pawn shop, at an architecture client's residence; Dali is everywhere. Now, a new and fresh way to look at the artist, in an honest way.

Early into the book, Grenier sheds light on Dali's fantastic imagination, where in his autobiography, The Secret Life of Salvador Dali, he fills pages with made up stories. In one of them, we are "informed" of his brother, also named Salvador, who was better at everything than him and smarter. Dali submits that he lived in his brother's shadow.

"My brother and I resembled each other like two drops of water, but we had different reflections. Like myself he had the unmistakable facial morphology of genius. He gave signs of alarming precocity, but his glance was veiled by the melancholy characterizing insurmountable intelligence. I on the other hand, was much less intelligent but reflected everything." The Secret Life of Salvador Dali (Autobiography)

The shadow of a brother who turns out to have passed at 21 months young. Grenier sees this duality as a constant theme throughout the artist's life in his attachments to other contemporaries like artist Andre Breton, poet Frederico Garcia Lorca, and ultimately his wife Gala. From fantasies of a double, to a system of finding grounding forces in his work and life in these counter characters. It was a form of stability for the artist. But then given these fabrications are we to take anything else we think we know about Dali with a grain of salt? Yes, but only if we were to accept that salt was the rarest commodity on the planet. Everything he did or said was intentional.

[caption id="attachment_64874" align="alignnone" width="430"] Venus De Milo With Drawers, Salvador Dali/Marcel Duchamp[/caption]

Venus De Milo With Drawers, Salvador Dali/Marcel Duchamp[/caption]

Grenier takes us through Dali's creation of Dali. As a student of the writings of Doctor Otto Rank, he creates a myth around himself probably based on Rank's notions of artistic genius, and what constitutes a hero. The latter includes a foundation of a glorified birth and youth, which Dali embellished to coincide with the anti-heroic character Dali. Grenier digs into his biggest influences: Picasso and Freud, and his close relationship to predecessor and Dadaist artist Marcel Duchamp, with whom he created works together, and under each other's names. For example, the Venus De Milo With Drawers is created by Duchamp but credited to Dali. She chronicles his association and ultimate departure with the surrealist movement, with which people mostly associate Dali. She writes about his political affiliations, from communism, to his ultimate disillusion with the red movement, to Dali's time as fascist supporter of Spanish dictator Fransisco Franco; all in the end seeming like antics.

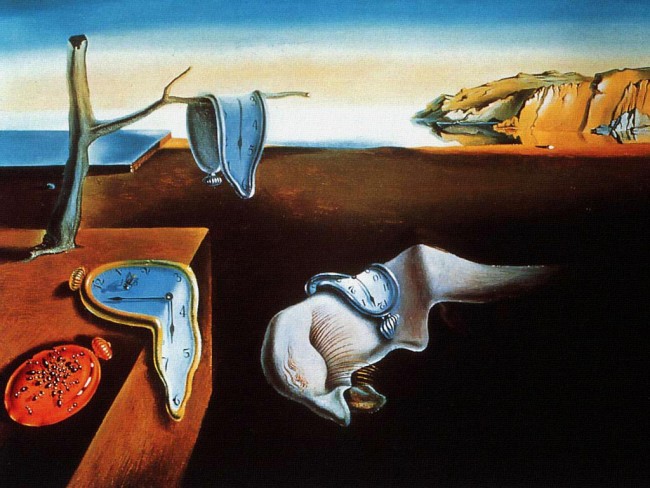

[caption id="attachment_64882" align="alignnone" width="650"] The Royal Heart, Salvador Dali; For the Love of God, Damien Hirst[/caption]

The Royal Heart, Salvador Dali; For the Love of God, Damien Hirst[/caption]

Dali was a living work of art. The life story and character he created became an exhibit onto itself. This influenced - and still does - artists like Banksy, Jeff Koons, Damien Hirst, Bertrand Lavier, and others who claim and do not claim him as a major influence in his ability to manipulate existing images and objects, and in the creation of his alter ego. Even outside of visual arts, people like Paul Reubens (Pee-Wee Herman), Andy Kaufman, Prince, and Rick Ross, among others, are preceded by Dali in their submission, at least to the public, to the artistic personality they created. Warhol, for example, learned and lived what he absorbed from Dali, including the importance of being a spectacle, of working outside of art as in advertising, of using other peoples images to create something new, making movies, setting up your own magazine, appearing on TV, and having that iconic thing that makes you identifiable visually: Warhol's Wig = Dali's Radar Moustache. Dali taught us all it was OK to BE anything, and to keep people guessing.

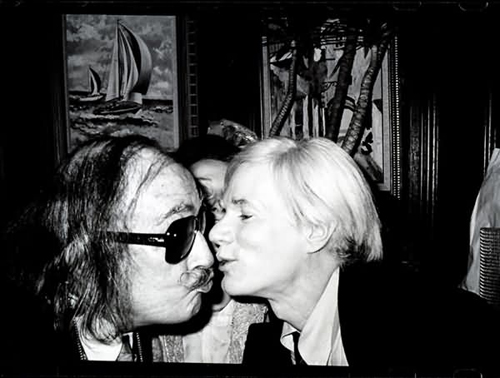

[caption id="attachment_64888" align="alignnone" width="545"] Salvador Dali and Andy Warhol[/caption]

Salvador Dali and Andy Warhol[/caption]

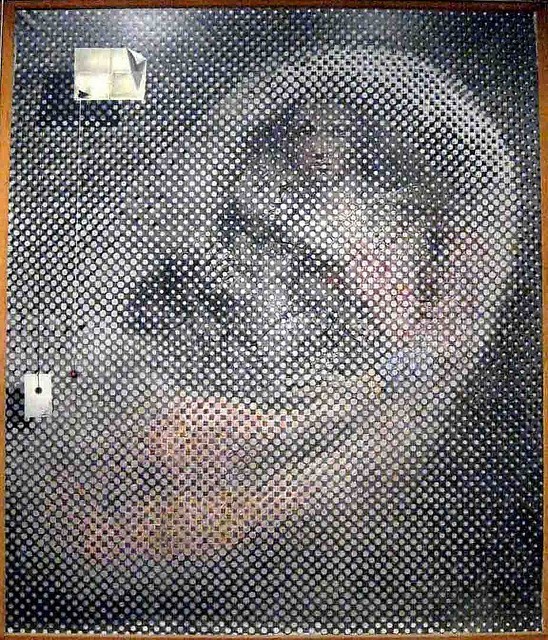

[caption id="attachment_64887" align="alignnone" width="548"] The Sistine Madonna, Salvador Dali[/caption]

The Sistine Madonna, Salvador Dali[/caption]

She documents the artist's decline in popularity from his last decade through more recent times where in 2004, the 100 year anniversary of his life, there were no major retrospectives of his work. None in France, and the Tate Modern, London, and MOMA, NYC barely celebrated in exhibitions relating his work to film. But even in the beginning of his decline he was breaking ground for future artists. In 1960 artists including Andre Breton, founder of the Surrealist movement, wanted his work The Sistine Madonna removed from the Surrealists' Intrusion in the Enchanter's Domain for being holy and naive. Later, the very Catholic Dali's work, which the loudest voices in the Surrealist movement dismissed, becomes known as the precursor to the Pop movement. And through his fall from the graces of art critics, in 1979 his exhibition at Paris' Pompidou Center is still the most heavily attended in the museum's history.

His use of very classical techniques, and of 'apprentices' in his studio setting up paintings for him, as well as his ever more difficult to understand antics, ultimately drove the physically, never spiritually, aging artist away from his influential position in the art world. But if you want to have a better understanding of modern art history you need but to look at Salvador Dali's work, as it resides in a great chunk of the entirety of modern art history and it's development. From his early obsession with Picasso, and all things Cubism, through Surrealism, to his product design, ad design, set design, to his use of trompe l'oeil and manipulation of existing images; the most consistent theme was his ability to continue to evolve and become something new.

[caption id="attachment_64891" align="alignnone" width="640"] Cuant Cau, Cau, 1972, Salvador Dali[/caption]

Cuant Cau, Cau, 1972, Salvador Dali[/caption]

Dali was barely bound by time, or era, or what was rational. His paranoia fed his art, and his art soothed his many neuroses. His mental illness became a tool in his process. Art was where he could ultimately be free and play with our understanding of the universe as well as his own. He was interested in the beginning of things, times, and places. While he explored the scientific and psychological achievements of his time, he also examined the birth, and rebirth, and the new forms of ideas and matter, and himself.

This book is a must read for anyone who wants to understand not just the artist, but also very important concepts of creativity, and his keen invention of celebrity, which in a reality TV era is definitely worth taking another look at. We learn how he continues to inspire. He reminds us that creativity is a place to be free from all of the rules, and as hard it is for us good people to avoid and ignore them, we must all try a little.

Catherine Grenier is an art historian and associate director of the Musee National d'Art Moderne-CCI at the Centre Pompidou in Paris. She has published other books including The Possible Life of Christian Boltanski.

You can purchase a copy of the book here.