Featured

INTERVIEW: Gilles Peterson

London-based DJ, Gilles Peterson, has championed independent music for decades. His eclectic selection, rooted in jazz and soul, has won him an enduring reputation as a quality music tastemaker with a loyal fan base all over the world. A club and radio DJ, festival curator, record producer, and head of Brownswood Recordings, Gilles Peterson has played a seminal role in the careers of artists such as Jamiroquai, The Brand New Heavies, Incognito, Roni Size, 4Hero and more recently Ghostpoet and Jose James among many others. His weekly Worldwide radio show on BBC 6 Music is syndicated to 13 stations around the globe.

I was fortunate enough to get a bit of time with the multi-faceted Gilles Peterson, amidst his hectic schedule and jet-set lifestyle. We had a quick chat at the newly refurbished Brownswood basement, where he has his studio and some of his treasured and enviable record collection. We talk about his forthcoming trip to New York, his new charity the Steve Reid Foundation and some of the nuances involved in being an international music luminary.

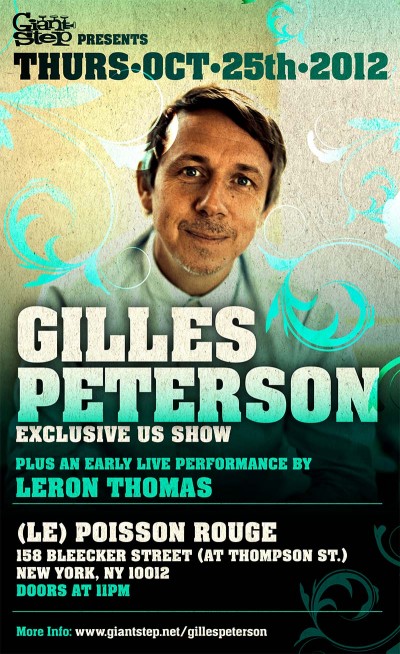

You’ll be DJing in New York very soon with Giant Step. When was the last time you were there?

The last time I was in New York was August 2011 and I played at Cielo, which is where I’d been playing more regularly recently. But it’s a bit of a lazy choice for a DJ because it’s quite an established club. That whole area has become a bit ‘Bridge & Tunnel’, and I think a lot of clubbers don’t like going to that area so much now.

There’s something interesting which someone told me about American night clubs and rules: if you go to a club and queue up, whatever you look like, whoever you are, you can’t be refused entry – unless, of course, you’re completely out of order. Whereas, in England or in legendary clubs like Studio 54, they’re known for their rigid door policy, and you wouldn’t get in if you didn’t look cool. The thing about America now, or has been for a while now, is that most clubs get shut down, not because of drug taking or because of other things you’d expect, but because they don’t let certain people in. They’re meant to let everyone in.

And what ends up happening in clubs as a result, as Francois Kevorkian said to me the other day when I asked him how his Monday nights were going, he said, “Yea it’s great, I love it, I love it, but every now and again you do get a bloke in a suit texting his friend on the dance floor.” (Laughs) That’s quite funny, I can imagine that.

I’m not doing Cielo this time, although it has the best sound system. I’m playing at a different place called (Le) Poisson Rouge, which is a nice place and is in what used to be the Village Gate, which was a legendary jazz club. I have loads of jazz records that were recorded live at the Village Gate.

So you enjoy DJing in the States?

I do, I like DJing in America, although I’ve stopped doing America in the sense of going for 3 weeks and then doing eight or nine shows. Now I just go to LA, New York, San Francisco. Back in the day, I used to go to Detroit, Washington, maybe Seattle and Philly. Last time I was there, I played in Chicago – we had a good night there.

But what I like about American clubs is that, once people pay, they’re going to have a good time. They’re up for a good time. It’s a struggle living in America, people get less holidays, issues with health insurance. It’s tough. You’ve got to hustle in America, and with that comes good and bad things. So when it comes to entertainment, when people come to a concert or a club, generally people are really up for it. I’ve had only brilliant times there, and New York’s got that added twist of people from all around the world and the New York dancers, who are amazing!

The first few years when I first started coming to America, I was a bit freaked out. I’d be thinking, “Oh my god, this is where Gil Scott-Heron used to walk around.” This is what I’ve loved all my life – the music, spirit, whether it’s the hip-hop or KRS-One or disco. And it’s always been weird seeing my name in big lights. And I remember going there back in the day with Jamiroquai and in places like the Supper Club. It’s been kind of twisted, almost surreal.

But New York has changed – post-9/11, post-Giuliani. It’s a different place now, and New York has been slightly overtaken by LA in the last few years in terms of the music that I do. Of course, California has KCRW - a good radio station. There’s been this kind of movement, whether it’s Stones Throw or Brainfeeder - significant music scenes that are closer to where I come from, and people know me better in LA. In New York, I suppose the coolest thing it’s done related to more where I’m coming from is the LCD Soundsystem, James Murphy. That’s probably more where I’d be in my comfort zone in New York, apart from the traditional stuff like Louie Vega. But in the more contemporary, younger thing, I think there’s more going for me in LA. But Brooklyn has got that hip-hop thing, which is good - some good groups coming out of there.

I’ve had some of my best nights in New York. I have a poster upstairs with a line up we did a few years ago –it was Steve Reid, Four Tet, Dwele, Jazmine Sullivan, Robert Glasper, Amp Fiddler.

Wow, amazing!

It was one night, and at the time, I think I was promoting the live sessions recorded at BBC Maida Vale. I gave Robert Glasper a call ‘cause he’s really good with back up singers. I asked him, “Can you put a band together so that Dwele can sing, and Amp Fiddler and Jazmine.” In one afternoon he just knocked it out and he was kind of our musical director.

I remember Jamie Cullum was in town on the same day, and he came and jammed with the Robert Glasper Trio - with Chris Dave and Derrick Hodge on bass. And Jamie Cullum’s bass player was a little worse for wear after a few drinks late in the night (laughs), and he wanted to borrow Derrick Hodge’s bass, but Derrick Hodge and the boys didn’t know who Jamie Cullum was, so it was all a bit awkward, which was a really funny story.(Laughs)

You also have a live performance at your New York gig?

Yeah, we’ve got some live music. We’ve got a brilliant singer out of Brooklyn called Leron Thomas, who I’d been playing a bit. So, it’s not just me, ‘cause I always want to incorporate all the stuff I love about America or whatever town I’m in.

When I go to places like New York or wherever, I always want to make the most of it and meet people, encourage them and do what I feel inspired to do, amongst others, by people like Steve Reid, who was such a collaborative guy. He always believed in doing things with people, experimenting, and out of experiments come positive energy. Steve was all about sharing and trying stuff out.

Sometimes you can get too stuck in your own comfortable little zone and think, “I’m doing ok, I’m doing ok,” but you don’t actually get out of your comfort zone. You know, there’s no point in me getting a warm up DJ who’s not really good, and then I come on and bang it. (Laughs)

You recently started a charity, the Steve Reid Foundation. When did you first meet Steve Reid and how did you become friends?

I first met him way before he was signed to Soul Jazz. I was on Kiss FM, playing my mix of soul and jazz and electronic and whatever. I got these cassettes sent to me from Amsterdam and they were from this guy called Steve Reid. I already had his record Lions of Judah, which I probably bought second-hand in the late 90s or something. I had been getting into that more conscious, spiritual jazz thing. But I didn’t put it together at first. In my mind it was a great record with a great sleeve, but I didn’t think I was ever going to meet him.

Then I started getting these cassettes from Steve Reid, and they were really wicked. They were swinging and his drumming style was what I was really into – a bit trancey in a jazz way, sort of Coltrane-ish, swinging, 40-minute track - long, intense and rhythmically powerful. And he had beautiful handwriting. He always wrote a lovely letter with beautiful handwriting saying, “Dear Gilles, I love your show. I always get cassettes of your show and I keep hearing about them.” And I’m thinking “What?!” And his sh** was hot, and he knew about me! I mean, he was in his 50s and he was so hip that he listened to guys like me. I liked his stuff and I’d play it on the radio and that was that really. Next thing I know he’s signed to Soul Jazz. And because I had this relationship with him through these cassette tapes, I was asked to write sleeve notes for his record. So I did that and then we met in London and we did a few podcasts.

Steve was one of those jazz musicians who couldn’t make a living in America, so a lot of them came to Europe, as there was a better way to being able to maintain here. That’s the ‘brutalness’ of America - you’ve got to hustle to survive. So when you have a bit of money, you have a good time and enjoy it. But it’s a lot harder to live and to make it and to maintain success. It’s a tough place.

The second record was Daxaar, that’s the record I had to write sleeve notes for. I remember driving down the mountain in Tignes, France to London and I had busted my ribs, and it was an 18-hour drive, but I remembered I had to write the sleeve notes for it. So I was listening to the CD of the album all the way, driving from the mountains to London with busted ribs, and then I wrote the sleeve notes. So when I listen back to that it brings back lots and lots of memories.

He recorded that record in Senegal and this was one of the things that connected so much with me and my philosophy as a DJ: he was global as well. He went on a boat back in the day and spent time in Africa. A lot of the new generation of musicians love to talk about it but they’re like, “Oh no, we’re not going there unless we go business class.” (Laughs) Whereas this lot, the Don Cherry’s and the jazz lot, the pioneers - they just went there. These guys were hard core! And we can all learn from that.

And why did you start the Steve Reid Foundation?

Steve was a bright light in our skies that passed through many, many years. For people like Keiran Hebden and for many people that came across him, he was a very important inspiration. And when he passed away quite suddenly, I mean, he was unwell, but he was such a positive energy that we didn’t think that he would die. He was like, “Yea I got cancer, but obviously I’ll get through it.” He was that kind of guy. So, when he did die it was a shock to everyone and for me. And the way he died - it was quite shocking because it was rough for him, and he didn’t get the treatment that someone like him, I would’ve thought, deserved and should’ve gotten because he gave so much.

You visited him, right?

Yeah, I visited him in his place in Harlem, and it was just not the best way to go. I remember thinking, “Can’t we do better than this?”

He was part of a lot of musicians and artists, and people in general, who haven’t got the same luxury as people in other parts of the world do, and to a degree, even here [in the UK]. At the end of the day you’re here, and you give a lot and you get forgotten, you die and you pass away badly. I thought it was important to shed light on musicians and people who have given a lot to art and culture and try to support them because they tend to get forgotten about. Artists and musicians are always seen to be in the limelight and some people get envious of them, but only the 1%, maybe even less, really benefit from financial success. And many of them have given a lot - and it’s a struggle.

There’s a whole generation of musicians who are reaching that point now, the golden age for a lot of jazz musicians, and a lot of them have passed away already. A lot of musicians are getting to that stage where they need help and support. So I wanted to find a platform to shed light for these people and to basically help musicians in distress. That’s why we are working with the Musicians Benevolent Fund.

But to also shed light on the energy that Steve Reid gave to us all and that encouraged a new generation. There’s this double aspect - to support youth and up and coming musicians with knowledge. It’s early days still. I wanted to basically underline this great man, the use of his name - it tells us everything really.

And it’s an educational thing. There are so many people who get involved in music. For some people it’s a way out. For some people it’s a proper career choice. But there isn’t a great deal of education about music - about where you can go, how you can personally survive better within it, how you can survive in the longer term. So I think it’s important that there is a body that can start looking at those issues.

And you have some high calibre people involved as trustees of the charity?

Yeah, it’s great to have people like Theo Parrish and Keiran Hebden, and young people like Koreless and Floating Points. So it’s good, it’s early days, but it’s very exciting. On a lot of levels it’s important for people like Keiran, Theo and myself, who’ve had 20 years in the game and understand it. It’s important for us to take on the responsibility of doing something like this.

You ran the London marathon last year raising GBP£7,000. Are you going to do it again?

Yes, I think so. I am in training at the moment. There are a lot of things we’re going to do. We just need to keep things bubbling, keep coming up with ideas, keep exciting ourselves. I’m looking forward to the drum-athon, I’m going to talk to Tom Page about that. There are so many great drummers in this country. We might even start a Steve Reid Drummer of the Year Award at the Worldwide Awards or something. Drums are the basis of dance music actually, so it’s quite a key instrument but doesn’t always get the attention it deserves. And drummers are often the butt of people’s jokes in the music world. There’s a lot of jokes about drummers.

Really? Tell me one.

(Laughs) I don’t know. He’s the one who doesn’t get the girls because at the end of the night he’s packing his drums. It’s usually the lead singer or the guitarist. (Laughs)

You’ve found a new radio home with BBC6 on Saturday afternoons. How are you settling in?

It’s good, I’m feeling it, they like me. The figures are good, they’re letting me use Maida Vale studios a lot more and giving me a lot of support. It’s been amazing really, and obviously it’s great because it gets to be heard around the world. It was important for me to stay with the BBC because I do believe in it as an organisation and it’s always inspired me. It’s one of the great reasons that I love living in the UK - because there’s always been a high-endness with television, radio and the arts in general. Without the BBC it would be a sad place. Imagine life without non-commercial radio. For me to be one of the few people on the BBC, and I'm able to do fundamentally what I want - I have one of the most privileged jobs in the world and I really appreciate it.

And the new format of three hours, daytime?

Better man, I find as I’ve gotten older it takes me longer to get into sh**. I used to be able to do one-hour or one-and-a-half hour DJ sets. Now I have to do four-hour sets because it takes me at least an hour to get into it. With this show, even if the first hour isn’t always as good, I definitely get into it by the last two hours, so the extra hour is good for me. (Laughs) It’s good to be on daytime in England as well, and I’m breakfast time in New York.

One of your most recent projects at Brownswood is the Mala in Cuba album, which got critical acclaim both sides of the Atlantic. The first batch of vinyl sold out. What gave you the idea to bring the two together?

I do these projects with Havana Cultura and rather than doing a remix version of what I’d done on the first album, which was fun and fine, I wanted to do something on the second album, where I could bring in someone I was really into musically, but I didn’t know very well.

Obviously, I was very keen on the whole sound system culture and bass culture, which Mala is, more or less, one of the leading lights of. And we got on really well when we met. And I wondered what it would’ve been like to throw someone like Mala into Cuba and I thought it would be interesting. It could’ve gone either way really, because I didn’t know him that well, but he really lapped it up and we had such a good time over there. And it was good be with Simbad as well because he’s such a great communicator and people person. The three of us in Cuba was really exciting.

So, to be able to make a record in my studio, and for the musicians to come into his studio next where we set up Mala with his laboratory type thing - it was so cool. And he basically did his translation of what Cuba and the inspirations were to him, so it’s come out really well. And the album has had a very good response. I mean, we’re lucky because he’s a pioneer, so whenever a pioneer makes that kind of music it’s all very highly analysed in a way and I can’t wait now because we’ve got a show at the Electric in Brixton, and that will be a sell out, so 1,500 people watching - that will be amazing.

We’re going to have Danay Suarez over for that, who is the most talented singer I have ever worked with. I feel kind of bad saying that because I’ve worked with some really talented singers. She's got it all - she can kill anybody on a rap, and as an artist, and her voice. We were at EGREM studios in Havana and we had some spare time and we had half a day left in the studio and she was there and Roberto Fonseca was there, who is one of the best pianists in the world. And I said, “F*** it, let’s make an album!” Literally in six hours we made an album with Danay and him and a quartet. And one track is 18 minutes long, and it’s a four-track album. It’s a magnificent record - probably one of the best records we’ve ever come out with, but nobody knows about it. The funny thing is, the French media got it straight away. But in England they didn’t get it, but in France they went crazy. She’s kind of big in France through that, but over here [in Britain] people don’t know her. But when she performs people do know her because she’s that good. It’s gonna be a great evening.

Gilles Peterson will be at (Le) Poisson Rouge with Leron Thomas (live) on Thursday, October 25, 2012 from 11pm. Tickets sold here. Further details available here.